REFLECTIONS ON ART AND ACTIVISM

a lecture with accompanying slideshow that I gave at Bloemhof Gallery, Curacao on September 10, 2025

1. Introduction:

This is a very personal talk, in which I speak not as a political analyst, but as an artist who is deeply troubled by the horrific reality I am living in.

In this talk, I will ask questions: can I, as an artist who is living in present-day Israel – stay silent in the face of these horrors? And if not, how can I speak out in a critical voice in my art – without turning it into a political poster? How can I combine the two sides of myself – the introverted artist, and on the other hand, the political activist against Israel’s occupation of Palestinians and its annihilation of Gaza?

What I will discuss here is not a prescription of how one should combine art and activism – it is my personal solution to the questions that I struggle with.

I do not have answers for the conflict - I do not know the concrete steps to stop the bloodshed in Gaza and work towards a vision of a joint and equal society of Jews and Palestinians. But I know such a joint and just society MUST be possible.

In other words, this is a talk about my art – with a slideshow of my photographs and installations from the past 8 years.

It is a talk about the dilemmas of the artist living and exhibiting in Israel. Only indirectly is it about the occupation of the Palestinians and the war in Gaza. And this is not what I am here to talk about – Israel is in the center of the news all around the world, and you here probably know more than what the average Jewish citizen of Israel knows - or wants to know.

2. Art and Activism: questions:

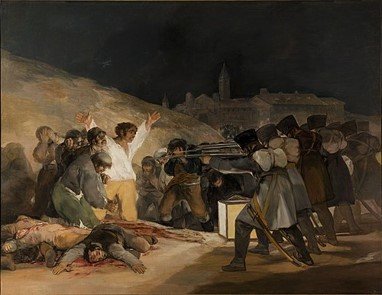

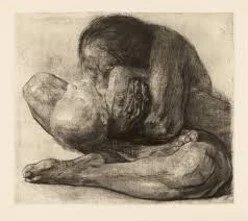

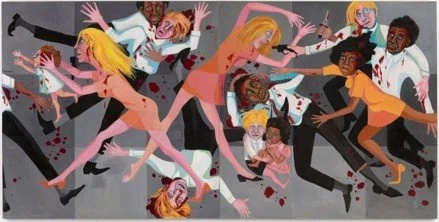

Throughout history, artists have grappled with the relationship between art and activism. Some works are very familiar – by Faith Ringgold, Käthe Kollwitz, Diego Rivera, Picasso, and Goya.

Can the artist stand passively by when she sees grave injustice in her society? Does the artist have the privilege to remain in her own inner world, absorbed only in dialogue with artistic questions? Or must the artist be a witness – or even an active participant – in social change?

And if the artist chooses to speak out, does art have any real influence beyond the art world? Can it change reality? Perhaps not directly – art may not change policies or structures – but it can raise awareness, provoke empathy, spark debate. That may be its role.

Another dilemma: how to avoid turning art into a political poster or manifesto. Political statements must be clear and to the point, while art has layers – surfaces and depths, ambiguity and resonance. Art can touch the viewer, raise questions, stir unconscious associations. But does political engagement compromise artistic integrity?

And another question: what distinguishes between documentary photography and art?

In more recent debates the complex question is raised: who has the right to depict injustice or suffering? How to avoid exploiting suffering for emotional effect – what some call “poverty porn.” How to ensure one doesn’t appropriate the voices of marginalized communities.

***

3. The two sides of me:

It is only at the age of 40 that I came to art. Before that I studied and worked in anthropology and then architecture from a sociological perspective. I had always dabbled in painting and drawing but never considered myself an artist.

It happened suddenly - while on a visit to the USA, in the desert of New Mexico. It was on a drive through the desert near the village of Abiquiu where Georgia O’Keeffe lived and painted. I stopped the car, and walked into the womb-like space enclosed by a striking rock formation, known as the White Place/ La Plaza Blanca.

There, I had an epiphany. The place struck me deep inside my body. I realized this was exactly where Georgia O’. Keeffe had painted her famous painting The White Place, and I was seeing not her painting, but what gave her the desire to paint. At that moment I knew that I must give voice to the artist in me.

These are two sides of me, that I struggle to reconcile. There is the side that wanted to bring about social change –and that led me to the study of sociology and to apply its insights in architectural design. And the other, the inner oriented side – that finally found its expression in visual art and the writing of creative nonfiction.

The tension between these two sides is also the central theme of this talk: how to find a resolution between art and activism.

*

Three years after I started to paint, I had a number of exhibits of my drawings and paintings, of skulls and landscapes, many inspired by Georgia O’Keeffe.

Photography came much later. Even though I come from a family of photographers and filmmakers, I always felt it was their territory and never thought of doing photography seriously.

I only started to photograph in the digital age, after I began to hike in the deserts of Israel, Egypt and Jordan.

The desert speaks to me in a very bodily way, touches on the subconscious, it opens us so many levels inside of me. I photograph the cracks and crevices, the gorges and canyons - all those hidden spaces. And the textures and the dance of the rocks.

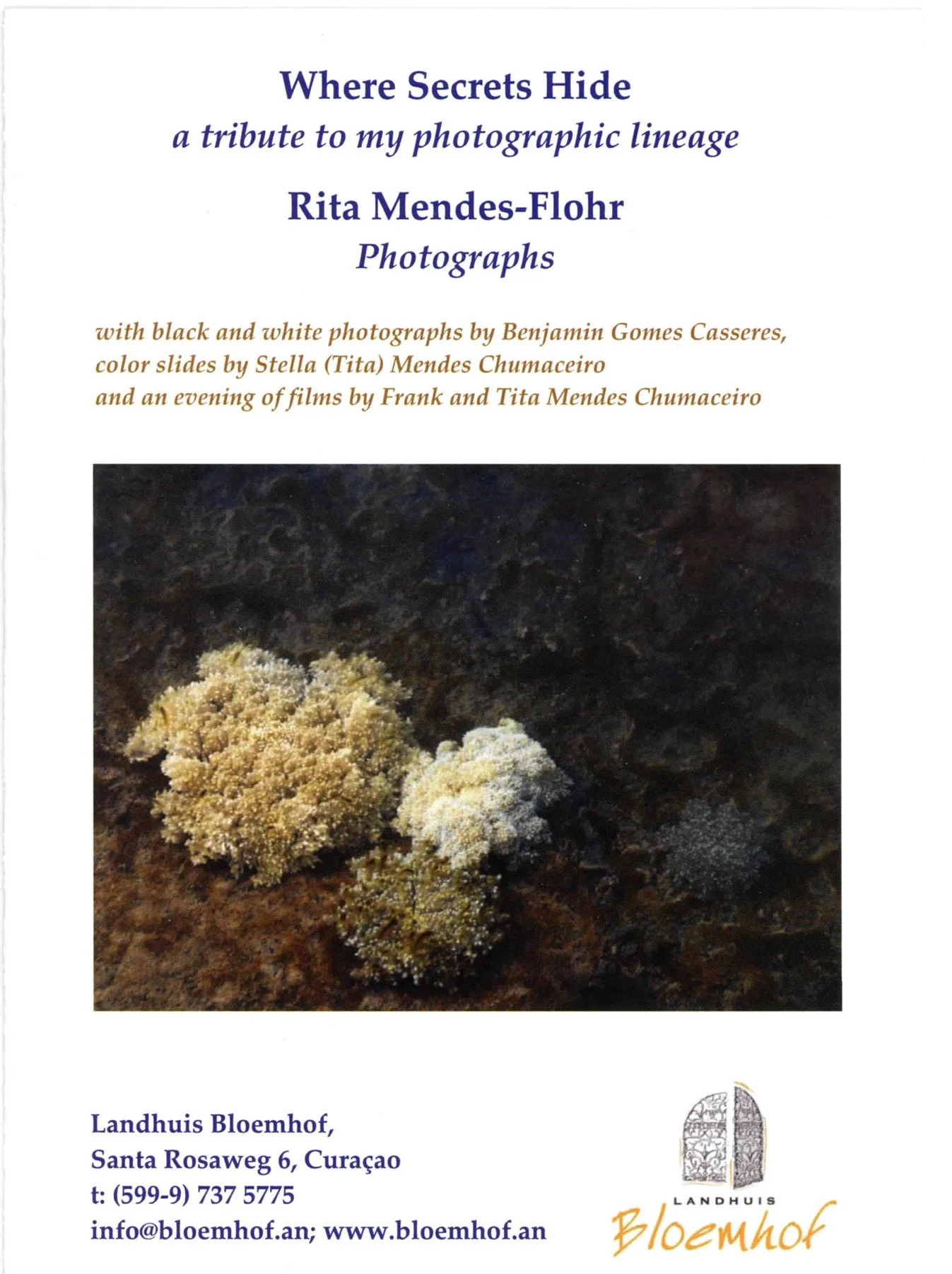

4. Bloemhof exhibit in 2010:

And I photographed on my visits to Curacao, when I hiked in the mondi with my brother Fred, completely off-trail – making our way through the wabis and infrou - because there were no marked trails in those days, only on the Christoffel – perhaps only goat trails.

Today I am glad to see how hiking now has become popular trend, with several hiking groups and many trails.

In fact, my first photography exhibit was at Bloemhof, in October 2010 with photos of my walks through the mondi in Curacao. I chose to turn my exhibit into a tribute to my photographic heritage showing the black and white art photography of my grandfather Benjamin Gomes Casseres, the films by my parents Frank and Tita Mendes Chumaceiro, and my mother’s color slides.

(see more on my photographic lineage: https://rozenbergquarterly.com/photographers-grand-daughter/)

5. Desert of Plenitude

Since 2017, I have been a member of a cooperative gallery that is run by artists as a nonprofit - where I have already had four solo exhibits and participated in quite a few group exhibits – with my photographs and installations.

The work I do is personal, intimate, bordering on the abstract. I seek to see under the surface, beyond what the eye recognizes, beyond the representational – to evoke associations of the unconscious.

These photographs are from an Artist’s book called: Desert of Plenitude that I exhibited in 2024 in a group exhibit. This is the work that I would love to be free to do.

6. Activism:

But, as I said before, there is another side to me – the side that wants to change the world, that opposes social injustice - that took me to sociology before I allowed the artist in me to come out.

I left Curacao in 1965 to study in the Boston Area. It was the second half of the sixties, the time of demonstrations against the Vietnam war, the struggle for civil rights, the beginnings of the feminist discourse, and the rise of Black Power. This is what consolidated my social and political consciousness. I am child of the Sixties.

After five years in the USA, I settled in Jerusalem in 1970, with my Jewish-American husband Paul. Coming to Israel was his dream, stemming from his ideals - of combining his Zionism with socialism in a just society that would include Jews and Palestinians with equal rights. Coming from the sixties, I shared his political views - though I did not come out of Zionism, like he, but was excited about the adventure of living in what I saw as a young, pioneering country.

At that time, it was only three years after the 1967 war, it was still a very different country than it is today. Palestinians in the occupied territories were much freer to move around, and cross into Israel, there was no separation wall - yet – that came after the second intifada in the early 2000’s. There were hardly any checkpoints on the roads and many Palestinians worked in Israel proper and spoke Hebrew fluently. True, there was an occupation, but the oppression was much milder - and certainly less visible.

Slowly the occupation became more and more oppressive, and I tried to find a way to make a difference.

I joined Women in Black’s weekly demonstrations of women wearing black and standing in a Jerusalem intersection, with black signs saying: Stop the Occupation. That was in response to the first Intifada in 1988, and I stood there every Friday at noon for seven or eight years.

After the second intifada, in 2000, when the Separation Wall was being erected, I joined the direct-action group MachsomWatch of women that would go out to the checkpoints and report on what was happening in the many roadblocks and barriers, as movement of Palestinians from the Occupied territories became more and more restricted.

Around 2016 I joined another direct-action group, that accompanies Palestinian shepherds as they take their sheep and goats out to graze. This was in an attempt to stop attacks by violent settlers from illegal outposts that seek to drive aay the shepherds and small farmers out of Area C- the area of the occupied West Bank that is administered by Israel, according to the Oslo accords.

These settlers were supported by the army - that was supposed to protect the Palestinians in the occupied territories, according to International Law.

Since the start of the Gaza war, the settlers have become more and more violent, making it impossible for the farmers and herders to go out into their fields, even causing some small herder communities to be abandoned altogether, because of the violence against their homes and herds. While the Army was just looking on, never arresting the violent settlers - often arresting the Palestinians instead.

7. How to reconcile between art and activism:

Must I separate between myself as a woman committed to social justice and an artist who wants nothing more than to spend all her time on a journey into the subconscious? Is there a way to bring the two sides of myself together?

Sometimes, art can serve activism indirectly – for instance, by donating a work to raise funds. Just this past August I contributed to an art sale supporting World Central Kitchen’s work feeding the population in Gaza. I am glad to say my piece from the Black Sabres series was sold.

- At other times it is about signing petitions as artists, writing op-ed pieces, or speaking at demonstrations – and perhaps performing artists and the more famous visual artists and writers among us have a greater impact in influencing opinions.

But is it possible to do art that itself addresses social and political issues?

8. Antea - Feminist art gallery

One possible solution to this dilemma of art and activism evolved in my work with the Antea Gallery of Feminist Art that I founded in 1994 together with another artist, Nomi Tannhauser, in order to bring about art exhibits that address feminist issues.

The idea was not just to show art made by women, but feminist art - art that raises questions about the place of women in society. So here we started to discuss social issues through art – such as violence against women, incest, women’s body image, women and the beauty industry, gender and sexual orientation, and especially giving voice to women from under-represented social groups – like Mizrahi Jewish women whose families immigrated from Moslem countries, and Palestinian women.

This did not mean that the art itself would always be politicized, “mobilized” – it could very well be evocative and personal, and still be exhibited in a context that raised social issues, broadening the feminist discourse by being accompanied by critical texts and, it is very important to add, discussion evenings where the issues raised by the exhibit, that might only be suggested in the art, are more explicitly examined.

In 2019– Nomi and I curated a huge exhibit to mark 25 years since founding of the Antea Gallery – with 100 artists – mostly women but also about 10 male artists who by this time in history, also came to refer themselves as feminists. The subject of the exhibit was a feminist interpretation of The Dress. It was called Her Dress, Her Symbol – noting that an icon of a dress is still used to represent women – for instance to mark women’s toilets.

9. ESTA BUNITA BO TA – how pretty you are

This is the work that I created for our Dress exhibit: it has a title in Papiamentu: Esta Bunita bo ta - how pretty you are.

I found these pretty little dresses among my mother’s belongings after she passed away. White, meticulously hand-embroidered dresses with fine lace work and tiny mother-of-pearl buttons that a little girl must take care not to dirty or tear by climbing trees and running wild across the yard, something that was especially difficult for me, as one who preferred to play with the boys.

I must have worn these delicate dresses - with a ribbon in my hair. And as it goes in our family, my mother would have worn them too, and who knows, perhaps her mother as well. All three of us grew up in a macho Latino culture where a girl is kept in the house, taught to fear the outside world where friendly but devious men roam the street (or even hide inside the house?) and will surely lure her with sweet words and a luscious shell, a kokolishi. [note, I will come back to this work]

10. Hedge of Thorns: group exhibit in 2017

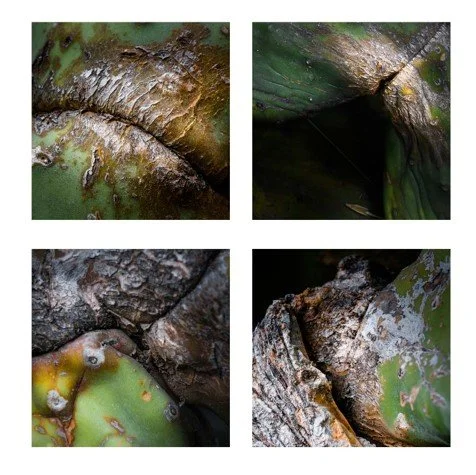

My first work that relates to the Palestine-Israel conflict centers around the Sabra cactus – and whose ripe fruits are delicious to eat.

The prickly pear cactus, opunta ficus indica, carries weighty, though very different, symbolic meanings for two peoples, Jews and Palestinians, and plays a prominent role in both Israeli and Palestinian art.

Yet it is, ironically, itself a displaced plant, originating in Mexico. And even more ironically – the reason why it was brought to the Mediterranean is because of an insect (cochineal) that feeds on the cactus and produces a red dye, the carmine pigment - that was very much valued at that time. But ultimately, the insect kills the cactus.

On the one hand, Israel-born Jews call themselves ‘sabras’ – like the cactus fruit - prickly on the outside, but sweet inside.

On the other – the cactus hedge is often what remains of Palestinian villages uprooted by Israel – The cactus holds on to the earth tenaciously, refusing to be eradicated.

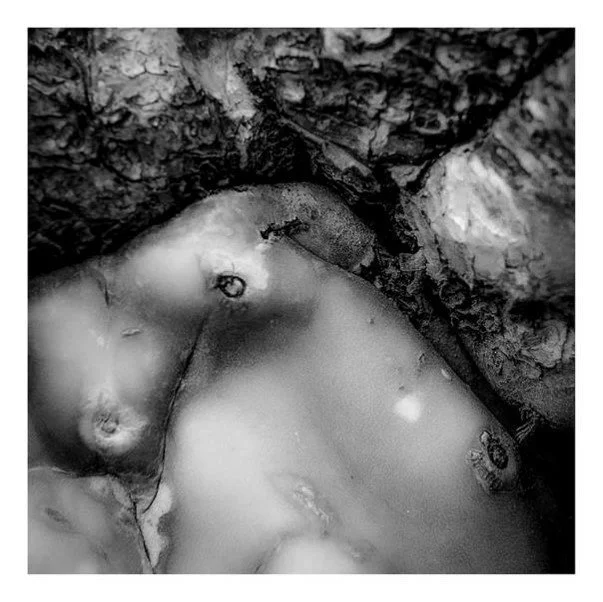

In this series, I chose to photograph the sabra hedge from very close up, penetrating into its inner landscape, turning my gaze on its scars, wrinkles and blemishes and uncovering their aesthetic power and sensuous associations - in a world where the tyranny of beauty and false perfection reign.

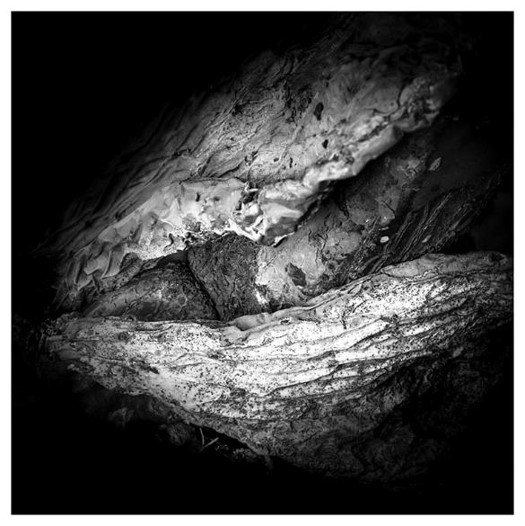

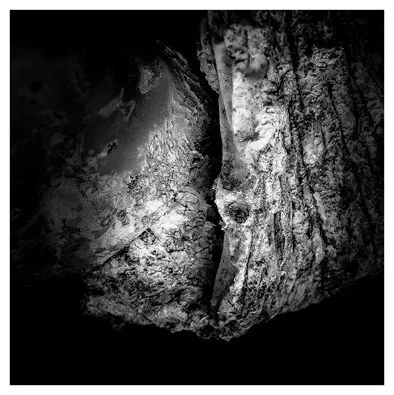

11.Black Sabres - 2020 solo exhibit

In my solo exhibit Black Sabres, in 2020, I turned my photographs of the sabra cactuses into black and white - and they became more abstract, less easily recognizable as a cactus, but arousing other darker associations, like aging and decay.

12. The Jordan Valley Just before:

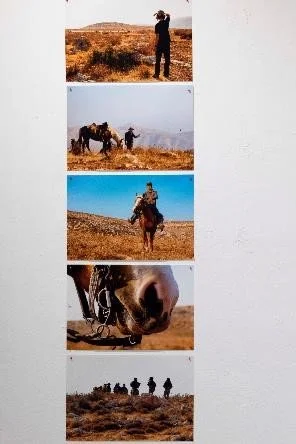

In my Black Sabres exhibit, I wanted to include the photos of my activism with the Palestinian shepherds that I, and other activists, accompanied on their grazing outings, in an attempt to stop attacks by violent settlers from illegal outposts that seek to drive away the shepherds and small farmers out of Area C.

The Jordan Valley Just Before - Just before what? You might ask. At that time, I thought Just before annexation by Israel.

But Israel is cleverer than that, as passing such a law to annex the occupied territories would increase international protest. Instead, it lets the unruly settler youth do the dirty job – of making life impossible for the herders and farmers, so that they will have no choice but to leave their communities.

13.Black Sabres - Inner Journeys in a Burning Reality:

So I showed works from two series, Black Sabres and The Jordan Valley, Just Before, based on two very different approaches, and exhibited the two series in an interwoven way.

And called the exhibit: Black Sabres – Inner Journeys in a Burning Reality.

Are these photos art or documentation? Can I create art that is more explicit in its political statement, and still be art? How to turn the documentary photos into art?

If I bring a more intimate vision to these photographs – for instance, by capturing the magic of the early morning light - will I risk making them too esthetically pleasing, thus beautifying an oppressive reality and trivializing the grave issues?

Or, precisely by focusing on the breathtaking landscape, on the sense of freedom to roam, the photos will emphasize what the Palestinians stand to lose? Would the esthetics of the works beckon the viewer to take note, and ask deeper questions about how the Jordan Valley is slowly, but deliberately being emptied of its native Palestinians?

Furthermore: Our artists’ not-for-profit, cooperative gallery was publicly funded by the Ministry of culture – so an entirely different question was: Can I show these photographs in a publicly funded gallery that would risk its funding if critical issues are raised that do not find favor with the ruling powers?

15.Art and Activism – zoom talk:

I want to emphasize the importance of discussions that are raised by an art exhibit – even when the art does not explicitly spell out a social or political issue – it raises questions.

The exhibit brought up many questions that were discussed with visitors coming to see the exhibits – as well as in a panel discussion with several other speakers beside myself. It was during the Covid restrictions; therefore, this discussion was held on Zoom and the text of my presentation was later published in the Palestine-Israel Journal.

(see link:https://www.pij.org/articles/2073/art-and-activism-dilemma-dialectic-duet ).

Perhaps what ties the two series together is the Palestinian concept of sumud, translated as “steadfastly holding on”. On the one hand, the black and white extreme closeups of sabres* relate to the prickly pear cactus hedges that stubbornly persist around the remains of Palestinian villages in Israel, refusing to be uprooted.

On the other, the color photographs in this exhibit show the Palestinian Bedouin in Area C who persevere in going out with their sheep in the face of the encroaching annexation of their lands.

16.Black Sabres – the installation:

As a centerpiece of the exhibit, I created an installation of actual sabres leaves – or pads - that I cut off the living cactus and spray-painted them black and their fruit red. I thought I had burnt them, ‘killed” them –

17.However….

A remarkable thing happened in the gallery. After about a week of lying on their low wooden stage on the gallery floor, the black, torn off sabres leaves miraculously started to sprout new life!

Holding on, tenaciously, despite all the darkness, hope never dies.

18.The Little Prince in al-Udja: a lightbox triptych

The exciting thing about being a member of an artists’ collective is you are invited to participate in group exhibits according to a theme and this encourages you to create works that you might otherwise not have created.

And so, for a group exhibit called My Second Childhood I was invited to choose a children’s book and to create a work that was inspired by it.

I chose “The Little Prince” because I am a lover of deserts. On my travels, I have roamed through the Great Sand Sea in the Egyptian Sahara and imagined the place where Antoine de St. Exupéry had an emergency landing on his flight from Paris to Saigon and was lost in the desert - like the pilot in the book. It was possibly the place that inspired him to write The Little Prince.

It is no wonder the book is set in the desert, as the desert, with its vast, unknown spaces, inspires seeing the world as if for the first time – like a child. It is where the fox reveals the secret to the Little Prince, that “it is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye."

In my reading, the book holds a political statement. The Little Prince travels to many distant planets to visit all these powerful people – all men. Their puzzling behavior of domination, possessiveness, arrogance, pigeonholing, power games does not make sense to the logic of a child.

I placed the Little Prince in Al- Auja, Jordan Valley, Area C. He herds his sheep, while his meager grazing lands, at the edge of the desert, are steadily downsized, fenced in, confiscated by settlers, declared ‘closed military zones’, firing zones or nature reserves by the army and the authorities. Incomprehensible to a child. Not only to a child.

So, I believe that here I did succeed in taking the documentary photos of my activism, and turn them into a work of art.

19.Six Songs of a Lost Innocence – Oct 7 and the Gaza War:

In October 2023 Israel lost its innocence. On the one hand, Israel, the strong military state, was caught completely off guard by the invasion of Hamas forces, enacting a horrific massacre, with unspeakable acts of cruelty, that has been a collective trauma for the entire Jewish population, especially in the shadow of the Holocaust. Perhaps it is difficult for someone who does not live there to understand, and regretfully, this trauma is often denied or minimized in the foreign press.

At the same time, Israel turned from victim to the perpetrator of mass destruction and killing in Gaza – going way beyond the “right to defend itself” and the number of dead in Gaza is over 64,000 – the majority are civilians, women and children. More than 70% percent of the buildings in Gaza were levelled or made unhabitable - including hospitals, schools, universities, religious buildings. In other words, more than two thirds of the population have been turned into refugees - many of whom are starving.

The saying goes: when the canons roar, the muses are silent – we, artists, perhaps the whole population of Israel, Jews and Palestinians, were all paralized – for weeks. Many cultural institutions closed down, stopped functioning.

But after a couple of months of being in total shock, our gallery decided to make a statement and return to exhibiting art - and not to let the war kill the spirit. A world without the human spirit is a dead world – and we decided to hold a group exhibit, called “Continuing”.

I created this work – called Six Songs of a Lost Innocence - especially for that exhibit:

The photos of the Arum Lilly growing wild in my garden were taken in April 2010. The flowers were no longer in their prime, already wilting, drooping, dying. In this exhibit, I turned them into black and white images and composed a print of six different images.

I am amazed to see how plants can express such a wide range of emotional states, speaking a rich and nuanced language of pain and sorrow that is so fitting to these times.

20.When the canons roar:

I began to work on a new solo exhibit in the summer of 2023, several months before the war, and decided it would focus on my mother tongue – Papiamentu- and on my own mother – as well as on mother earth. However, the intimate subject of my planned exhibit lost all meaning after the carnage of October 7 and of the Gaza war, and I entered a period of deep paralysis.

It took a long time, perhaps over a year, but little by little, I started to dive into writing the texts of this exhibit and photographing my mother’s treasures.

Working on this exhibit became what kept me above water when the world around us was sinking, and during a difficult year on the personal level as well. Precisely the search to reconnect to my mother tongue, to find the place in which my creativity can take root and grow, is what gave me back my strength.

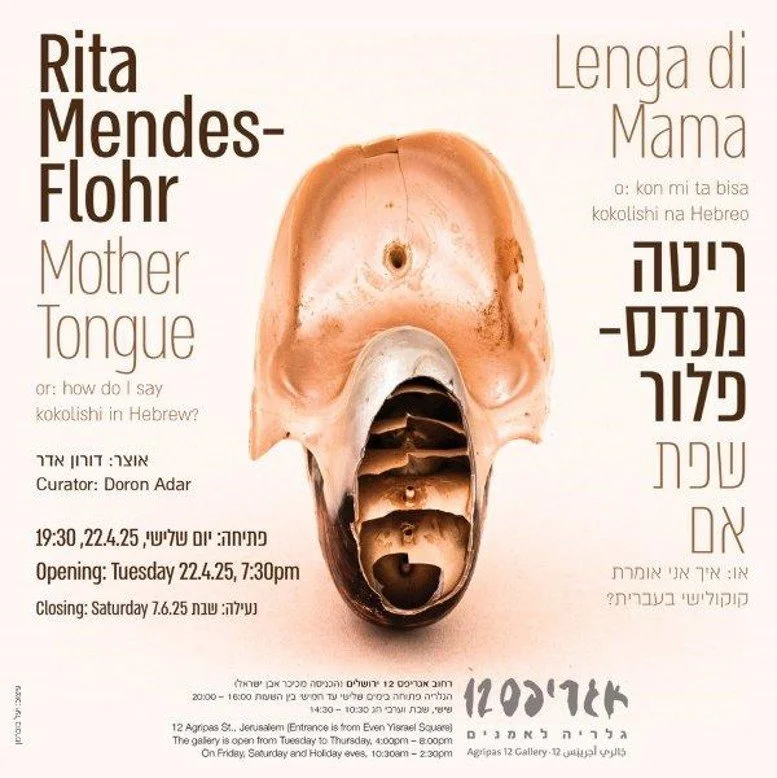

21.Mother Tongue – or: How do I say kokolishi in Hebrew - solo exhibit in April-May 2025.

Several years before, I wrote a text about speaking Papiamentu, and as texts are important to me, I wanted to make this the starting point of the exhibit.

I will read a few paragraphs from that text:

“The silencing of our mother tongue – whether by legal restrictions, cultural dominance, means losing an essential part of ourselves. It is the painful predicament of many of us immigrants, and of other uprooted people, when a primal part of us does not come to expression and cannot give birth to our creative selves. No wonder the word for uprooted in Hebrew, עקור, also refers to barrenness.”

(…) In my case, my mother tongue was silenced by the absence of other Papiamentu speakers in my vicinity (note: I wrote that text before international calls became free as they are today – so I had no one to speak Papiamentu with) –

Feeling that Curaçao means nothing to those who have never lived there and who do not know my language, I do not dwell on my background – I do not talk about where I come from (...)

And so, rather than allowing myself to feel the loneliness, I let that part of me go – I have erased it. It is a part of me that I do not speak about if I cannot speak from it.

(…) Until recently, I did not realize that I have been paying a price for the erasure of such a central part of who I am. Rather than being a stranger to those around me, I was a stranger to myself. (...)

Finally, on the plane, at my window seat, for which I always ask so I can see, and photograph, the island when we are landing, I realize I am shedding the layer of my everyday life in Jerusalem, like an overall, or rather a heavy spacesuit that cloaks my entire body and dictates my movement. It takes me a while to recognize that Papiamentu-speaking-self that is crammed inside, the way I think, twinkle my eyes, dance the tumba in Papiamentu. I regain a visceral quality, not just a language – all those things that get lost in translation.

(for the full text of Speaking Papiamentu, see: https://rozenbergquarterly.com/speaking-papiamentu-on-re-connecting-to-my-native-tongue/)

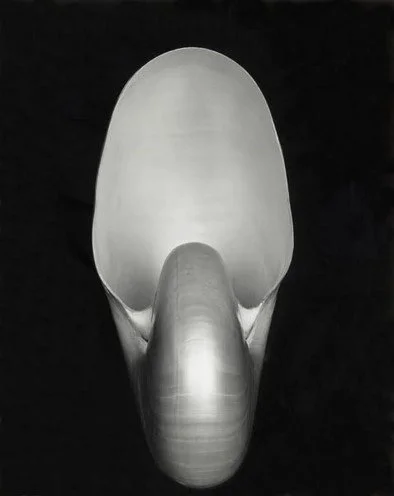

22. Kokolishi – Femmage to Edward Weston:

I chose the word Kokolishi in the subtitle originally for its sound, just a word I love to hear. That connects me to Curaçao. There are juicy words that I dance to: kokolishi, maribomba, wararwara, barbulète - they do not sound like any other language.

The kokolishi appears often in this exhibit – I do not give an explanation – perhaps it is a temptation, something to seduce the little girl? Perhaps it is the interiority, the secrets it hides? Perhaps it is the house, the animal’s home – the place where we feel at home, protected and warm?

In this work, I photographed a nautilus shell in the exact same position as the photographer Edward Weston photographed his famous black and white image. Except that color photograph is of a broken shell, where you can see its innards. The imperfection vs the perfection of the master photographer. I called it a femmage to Weston.

*

A word about my subtitle: How do I say kokolishi in Hebrew? It is not that I don’t know the word for kokolishi in Hebrew – but I was asking a different question here: how can I speak my mother tongue, while living in a country where I did not fully feel at home?

Perhaps it is through my art that I have to speak my mother tongue.

23. Esta Bunita bo ta - 2025 series (as part of my Mother Tongue exhibit)

As part of my Mother Tongue exhibit, I expanded on the work I had created for the Dress exhibit I spoke about earlier, creating a series with more little dresses and different shells, and printing the photographs in a larger format.

24.Mother of Pearl/ My mother’s Trousseau: (as part of my Mother Tongue exhibit)

I based the exhibit on the personal heirlooms I brought back with me to Israel after my mother died – at the age of 96, in 2009 – wanting to keep something that would recall her physical presence, that was touched by her body. It was a collection of her nightgowns, shawls, jewelry, intricate lace doilies, tablecloths, and evening handbags. I knew someday I would create a work of art with these treasures - her ‘trousseau’ – except that it was given to me, her daughter, not on my marriage but on her death.

My mother – a nature lover and hiker, a competitive swimmer in her late teenage years, and a painter – but all these she gave up, because of the social pressures of her social environment.

I see that her ‘trousseau’ expresses the feminine requirements of her social milieu, and where she tried so hard to be accepted, perhaps to the point of silencing an essential part of herself, her soul. I have come to act out, perhaps realize, her dreams of becoming a serious swimmer, avid hiker, and artist

Happily, in later years, she learned to express her artistic talents through her photography and the films she made with my father.

This installation: photos of her as a swimmer, and a collection of her slides – together with the many evening handbags that in my eyes are not very practical and can carry only a handkerchief and some make-up.

25.My mother’s nightgown (as part of my Mother Tongue exhibit)

And so I started to photograph her silk nightgown in the studio – in extreme closeup – seeing it like a desert landscape – seeking in the the same sensations I have when photographing the desert.

I re-appropriate her ‘trousseau’ in my own art, the way I explore the curves and crevices of a desert landscape, subverting it in a painterly language of sensuality.

26.I hear the Sea – mi ta tende laman (as part of my Mother Tongue exhibit)

The title: I hear the Sea - suggests a conch shell, a karkó, through which I can listen to the sound of the waves – the Caribbean Sea that is so far away.

Of course, this is not a sea. This is mother earth – the Judean desert in Israel. This is how I connect to the country as a hiker and photographer of nature.

This is how I am speaking my language = this is my language, this is how I speak Papiamentu when I am in Jerusalem.

27.A note about the Gaza War

– again, the familiar conflict between personal and political

MOTHER TONGUE is a very personal exhibit - in complete dissonance with this time, one of the bloodiest for both Israelis and Palestinians.

As I said earlier, I was completely paralyzed by the outbreak of the war – and only slowly was I able to continue my artistic practice. And it is precisely this turning inward, and searching for my relation to my Mother Tongue, that gave me strength to face the horrors around me.

But how to explain to myself, and to others, how I could turn inward, in these times of the October 7 massacre and the total annihilation of Gaza?

First of all, I realize that the exhibit speaks about displacement – of myself, but underlying that, of the Palestinians citizens of Israel deprived of their mother tongue through the Nation State Law, enacted in 2018 - that declares Hebrew as the official language of Israel – and relegates Arabic only to a special status language. It symbolically downgrades Arabic, which had previously been considered one of Israel’s two official languages.

And so, on second thought, perhaps the exhibit is not divorced from our current reality after all, as it asks, what is my place in this country where I have lived 55 years of my life?

A question that becomes more and more difficult to answer.

(link to my Mother Tongue exhibit

- all texts and images: https://www.ritamendesflohr.com/words#/mothertongue

28.CODA:

Black Sabres - 2025.

as part of a group exhibit called “Bleeding”

I was asked to participate in a group exhibit in August 2025 called Bleeding - a very appropriate theme for this time of so much bloodshed.

I created a new version of the painted black sabres installation with the red fruits. Compared to the version from 2020, in the context of the war in Gaza, it received yet another layer of meaning.

This time, the sabra cactus I picked and spraypainted black was affected by the cochineal insect – a plague that threatens the life of the plant.

As I break open the white spots of the cochineal that grow on the cactus, the red, carmine dye is released, the dye that was so valued by painters, the reason why the cactus was brought from Mexico to the Mediterranean. But now it is like blood on my finger.

however….

again, the symbolically burnt sabres are sprouting new life.

A symbol of hope for our conflicted region?

My website: www.ritamendesflohr.com