My photographic lineage:

I grew up surrounded by photography – my maternal grandfather, mother, and father were all avid amateur photographers and filmmakers. Countless photo albums could be found in our home in Curaçao, while movie screenings and slideshows were regularly held in our living room and at the houses of family and friends who would invite my parents to show their work. That was our entertainment in the nineteen fifties, long before television came to the island.

Photography was a natural part of my life at a time when it was not the case for many others, as it is today, when everyone carries a camera in their cell phone and visual culture dominates our life. Then it was a matter of privilege that not many had. On top of that, my father was the co-owner of a camera store, and so he and my mother had access to good equipment, and both my brother and I owned our own simple box cameras from a young age, upgrading our gear as we grew older. Still, I did not take photography seriously as an art until the digital age, when I began to feel I could have more control over my output.

It was only recently, as I started to post some of my family’s old photographs on Facebook, accompanied by stories from my childhood, that I began to think seriously about the many ways my photographic lineage had an impact on the directions I have taken in my life and the artistic concerns I have developed.

photo by my grandfather Benjamin Gomes Casseres - from the nineteen forties

Paito, as we all called my grandfather, began to photograph a few years before my grandparents moved from Curaçao to Cuba around 1912. We still have his albums with photos of my mother, her sister Luisa and their younger brother Charlie – mostly studio photos, often printed in sepia, with the children dressed up for costume parties and other special occasions. My mother told me Paito would set up a closed balcony in their house in Habana with curtains or a large painting of a landscape in the background. In 1929 my grandparents returned to Curaçao with their three Cuban-born children, where my grandfather continued to photograph – landscapes and people of Curaçao and especially his grandchildren - until his death in 1955.

In the summer of 2006, only a few months before my uncle Charlie died, I interviewed him about Paito’s photography and he made a drawing of the camera Paito used in his earlier years as a photographer, the Graflex – a pioneering camera with extension bellows – at a time before there were light meters, not to speak of those that are built-in.

Paito would send his photos to be developed in a laboratory in England and he would draw lines on the contact prints indicating where they should be cropped, sending them back to England with the negatives, to be enlarged. Long before Photoshop, he would ask the laboratory to add a sky from a different photo to one of his landscapes. It must have taken a very long time to get the finished photos when mail was mostly carried by ship across the Atlantic.

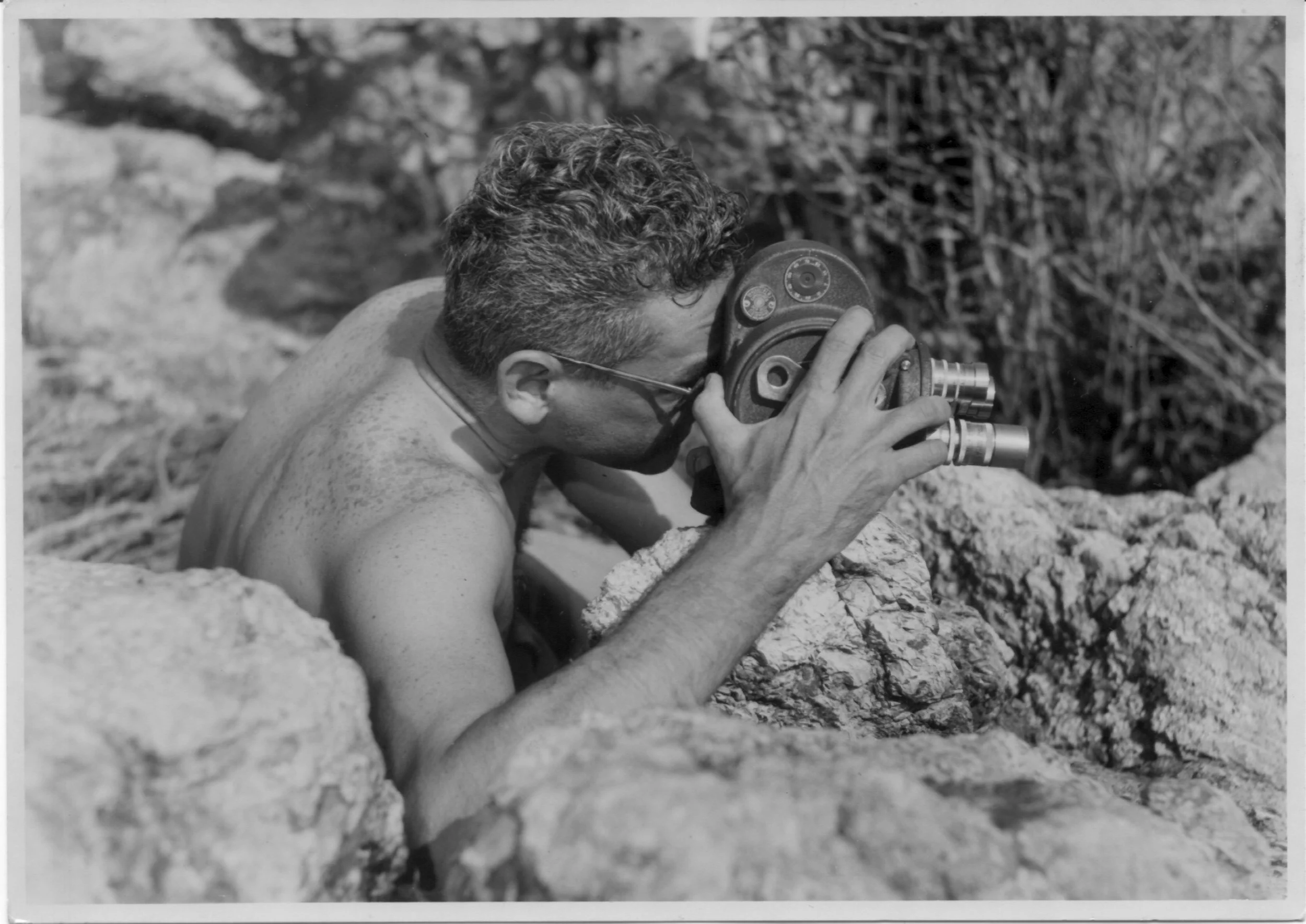

Pappie and Mammie started to make family films of my brother Fred and me as little children and went on to create a body of films with narration and music soundtracks they called “Curafilms”. Their studio was in our living-room and study, complete with an editing machine for splicing films and sound equipment, assisted by the writer Sini van Iterson in their very early days and later by others, most notably Jan Doedel as narrator and sound technician.

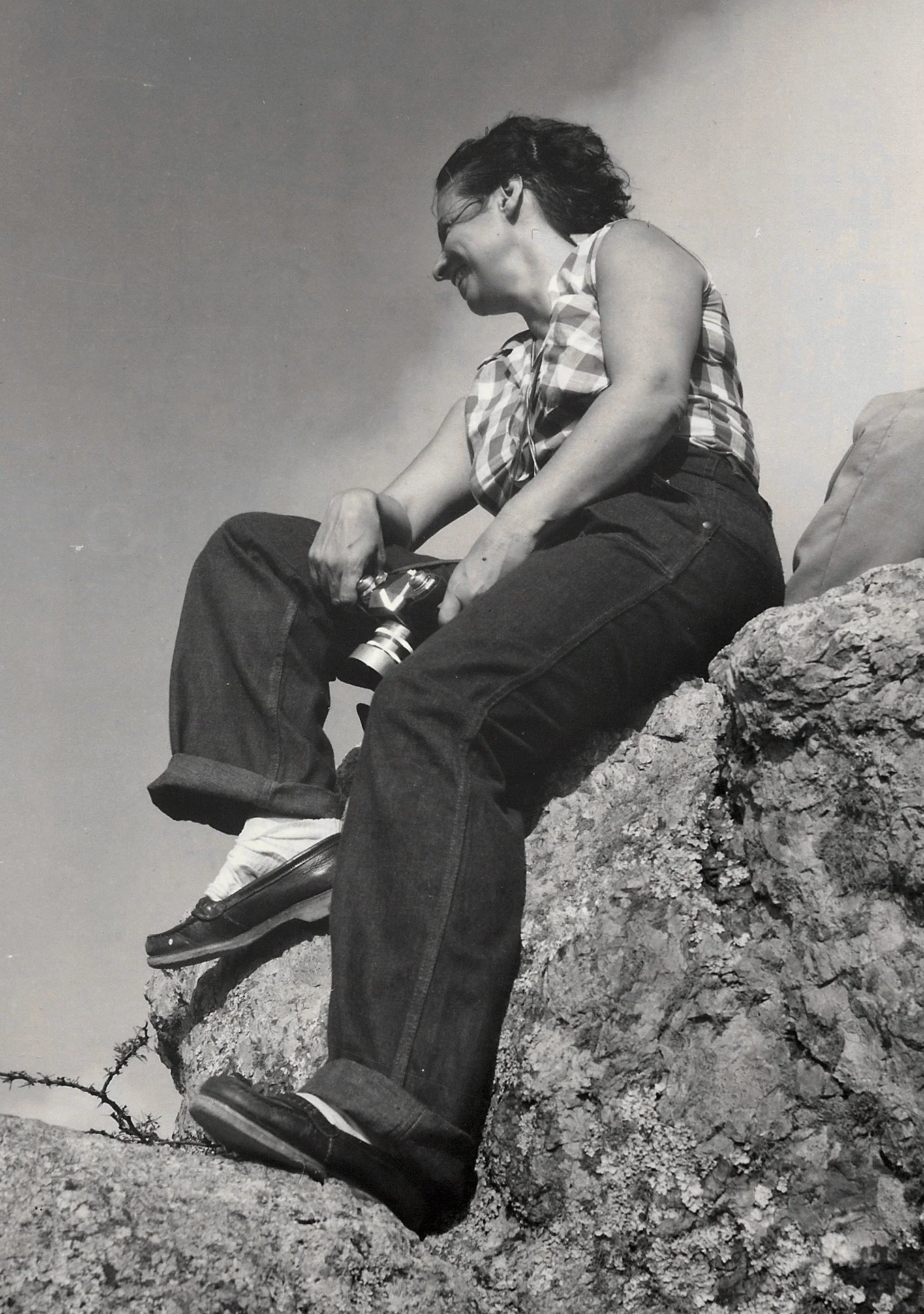

On all our excursions, Mammie took her own slides as well, having moved her artistic talents from painting to photography. Through the years, she won many prizes with her slides, and her flowers were chosen for a series of stamps of the Netherlands Antilles in 1955. In the nineteen-sixties she joined the wetenschappelijke werkgroep (the scientific exploration group) and continued to photograph while hiking to many lesser-known parts of the island.

In thinking seriously about my rich photographic background, I have found at least six ways in which it had a significant influence on my own development as an artist: the photographic excursions into the countryside; growing up surrounded by photographs and films; to be the beloved photographic subject; understanding photography as art; witnessing true teamwork; and most importantly, how the attitude of the photographer as both insider and outsider relates to my own search for the in-between, the under-the-surface.

a. The photographic excursion

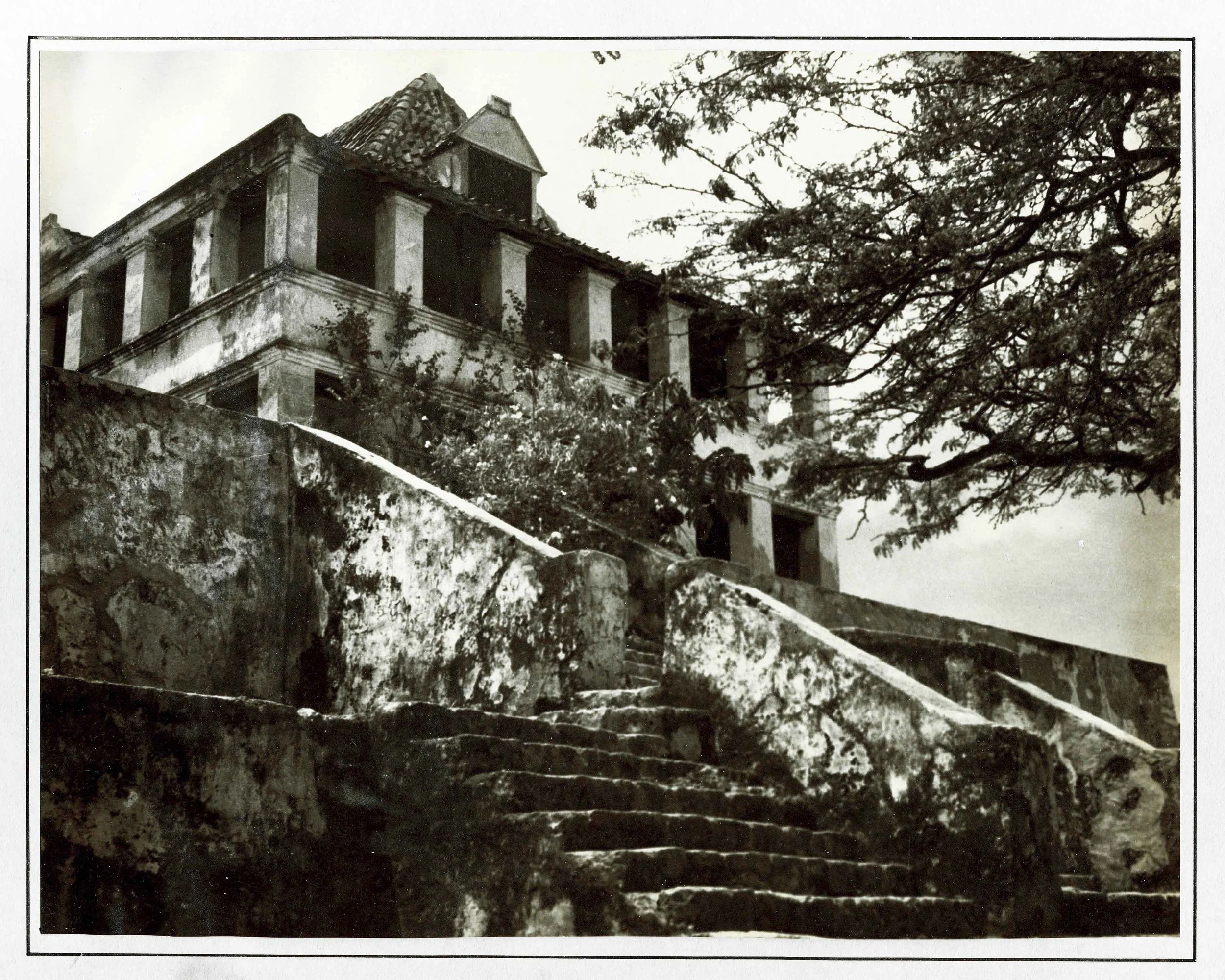

The many Sunday trips with Paito to the Curaçao countryside, where he took photos of old abandoned plantation houses and their shady groves of tall trees, the beaches on the far end of the island, the wild and rocky North coast, had sown the seeds of my own love of nature and spirit of exploration.

These photographic excursions continued with my own parents, Frank and Tita Mendes Chumaceiro, when they made documentary films about the island, in particular, the nature film Rots en Water in 1956, which took us to climb the Christoffel from Savonet (before there was a park that laid easier access roads and trails) and enter the cave of Hato with a guide carrying a torch of a dried datu cactus, and most of all, getting permission to go to Oostpunt, that huge property, almost of third of the island, that was in private hands, where very few people could enter.

photo by my grandfather Benjamin Gomes Casseres - from the nineteen forties

Access to many of the island’s natural wonders indeed depended on privilege – to have the right connections to people who owned private plantations, to get permission to enter what was private property and closed to most of the island’s population, often due to racial discrimination. All that, added to the fact that photography in those years was an expensive undertaking, and many could not afford the equipment, and the development, and printing of exposed film.

Owning a car that allowed one to travel on the dirt roads outside the city was also a question of financial privilege. Paito had a chauffeur who drove his shiny black car and who would clean off the dust and mud when he returned. I don’t remember if Paito would drive himself within the city, but on these excursions, it was Marty, the chauffeur who did the driving, allowing Paito to fully concentrate on his photography and not to worry about finding the way and getting stuck on the bumpy country roads.

These excursions in my early childhood fed my desire to seek the hidden, abandoned places, to discover a beach where I had never been before, climb a hill that was yet unexplored and to find our own path through the local wilderness, the mondi. A desire I shared with my brother Fred and we would go off into the mondi on my yearly return visits after leaving the island in 1965.

Mammie came into her own with the exploration group she joined in her fifties and sixties, her acting on her longing for her childhood in the Cuban countryside and naturally, taking many beautiful slides on those expeditions. Although I was not part of that group since I no longer lived on the island - I took that as an example and started to hike seriously also at a later age, while on a year in the USA, together with my family. Returning to Israel, hiking became more and more a way of life for me.

Until 2005, when I got my first digital camera, I did not photograph on my hikes, at least not seriously. It was my love of hiking that led me to photography, rather than the other way around like my grandfather, who sought out the countryside in order to photograph.

b. A treasure trove of photographs

In today’s era of digital photography and especially after the phone camera came into popular use, every event in life is recorded, and immediately shared on social media. But do we preserve these photographs? Do they remain for others to see, in later generations?

Paito’s photographs were always printed, inviting a ritual of looking at photo albums. The photographs were just preserved, but accessible, organized, and encouraging the ritual of listening to stories, memories, to imagine a childhood of a parent in a different country. Often as we sat on the floor near the cabinet where those albums were kept, listening to the stories recorded in those photos.

photo by my grandfather Benjamin Gomes Casseres - from the nineteen forties

I am fortunate to have grown up with such a wealth of photographs to document our family history, to bring back memories that have strengthened my sense of who I am, that have fostered a sense of security and connection to the past and to a loving family. It is a sense of grounding. Clearly, many others who grew up in less secure material and emotional circumstances, did not have the same visual record of their families and of their own early years, especially those whose lives were uprooted and had to flee, leaving all visual relics behind.

When I was writing my fictionalized memoir “House without Doors”, taking the reader through each room of the old house where I grew up, I created an album with all the photos I could find in my family’s collections. These photos helped me remember all the corners of the house, the places where we played, the rooms, the people who lived there and came to visit – and brought back that period in its richest details.

c. Being the subject of the photograph

photo by my grandfather Benjamin Gomes Casseres - of me age 3

I was the only girl among Paito’s grandchildren. He loved to say, “three males and one female” using terms in Spanish, “tres varones y una hembra” that refer to the gender of animals but were clearly meant in an affectionate way. The fourth grandson was born just a month after his death and was named after him.

I am fortunate to have grown up with such a wealth of photographs to document our family history, to bring back memories that have strengthened my sense of who I am, that have fostered a sense of security and connection to the past and to a loving family. It is a sense of grounding. Clearly, many others who grew up in less secure material and emotional circumstances, did not have the same visual record of their families and of their own early years, especially those whose lives were uprooted and had to flee, leaving all visual relics behind.

When I was writing my fictionalized memoir “House without Doors”, taking the reader through each room of the old house where I grew up, I created an album with all the photos I could find in my family’s collections. These photos helped me remember all the corners of the house, the places where we played, the rooms, the people who lived there and came to visit – and brought back that period in its richest details.

d. Understanding Photography as Art

Paito’s photographs were admired immensely, though I am not sure if anyone else who was not a family member or friend would see them, as his photographs were never part of a public exhibit – they were in family photo albums, to be viewed only in intimate circumstances. I do not even remember seeing them framed on the wall. Paito was known as one who knew how to photograph beautifully – though I am not sure if he was referred to as an “artist”. I always understood his work was different from the snapshots that others made, I could tell there was a lot more to these photographs that captured beauty, a different era, mystery, serenity, and longing.

As a child, I would observe how he worked with seriousness and devotion – never cutting corners. I noticed his patience, measuring light with an external light meter, figuring out the exposures, choosing the right angle to shoot. It was not a question of capturing the moment – but to look deeper and further into a place and time – all for just one final image.

photo by my grandfather Benjamin Gomes Casseres - from the early nineteen fifties

I must have understood at an early age, that is how you do art. That this is the seriousness with which the artist works. I am also one who does many revisions and go through of a long process to arrive at the final work, though I don’t believe I have the patience and sense of perfection he had.

Perhaps I also developed a sense of composition by looking at his photographs, intuitively understanding what made them special, as well as how he captured a sense of mystery, space and distance in his work. I certainly noticed his subject matter – a romantic preference for remnants of the past, old plantation houses, ruins of forts and towers, a lonely house in the fields, the peaceful atmosphere in the old groves of tall, shady trees – the hòfis – that he had set as the goal of his excursions, as well as his attraction to the old crafts, trades and festivals that were slowly disappearing even then.

As for my mother’s work, I was glad to realize while looking at her slides not long ago, that both of us were drawn to the more abstract salt formations in the saltpans.

e. Witnessing teamwork

“Curafilms” was a joint venture of our parents – the titles always said: “by Frank and Tita M. Chumaceiro”, without specifying the functions of director, cinematographer, editor, art director, sound designer. To have parents doing creative work, and especially when they do it together, was not the norm in the environment I grew up in. Though it was Pappie who held the film camera and physically spliced the film in the editing machine on the desk in his study, Mammie was a full participant in all the stages of production – sharing her creative insights; scouting locations; discussing the editing options and coming up with new ideas.

I was jealous that I could not be a part of the action in the evenings, when I had to go to sleep, and they were working in the study and living room right below my bedroom. In many ways it was also a family project, as our parents always shared their ideas with us, and most of the time, we were a part of the filming of each film, going on the filming excursions and the locations. This was especially so with “Rots and Water” that took us to all the wild, lesser-known places of the island. Even when I was still in elementary school, they would share their thoughts about the making of each film with us, and we were there to watch the film-in-progress when they projected it on the screen in our living room.

I think I learned from my parents the benefits and pleasures of teamwork, even though I am a loner, preferring to do the work by myself, not because I need to get all the credit, but rather out of a need to be self-sufficient and not to rely on anyone else. When I was a curator, and the director of the Antea Gallery for feminist art that I founded together with another artist, I worked closely with the artists we exhibited, as well as with other curators, when it was a co-curated exhibit. There is a tremendous joy in working together, and to inspire each other, and the feeling of satisfaction in completing a shared project, when the finished work is more important than the ego.

f. The photographer as both outsider and insider

photo by my grandfather Benjamin Gomes Casseres - from the nineteen forties

Looking at Paito’s photographs, I realize that what made them so remarkable is that he saw beyond the familiar, exploring the boundaries of what is seen with the eyes - what it means, what it evokes – that he sought to see its aura. It is an act of looking deeper and further into space and time. In his photographs of ruins and relics he conjures a whole era that once was and is no more; in his closeups he penetrates deeper into the details of what is; and in his landscapes he looks out into the distance, past the horizon.

The act of photographing required him to take a step back, to look from the outside, at a distance, with the attitude of the outsider. But it also required him to penetrate beyond the surface, to have the intimacy of the insider, to look lovingly, to acknowledge the other as a subject. In other words, his photography shows that he was both insider and outsider.

With this realization of the outsider/insider stance that is inherent in the act my grandfather’s photography, I have come to better understand my own relation to the medium, being myself both an insider and outsider to my native Curaçao, which I left in 1965 to study and where I return only as a visitor.

I arrive at the island with the eyes of the outsider, but with an insider’s familiarity. I am searching for something – perhaps of the past, perhaps of the hidden secrets that eluded me as a child yet continue to fascinate me today. It was in Curacao that I started to photograph seriously, continuing to deepen my photographic vision as outside/insider as I developed my art, seeking to look beyond the surface, into the interstices, deep into the unconscious.

***

Jerusalem, August 6, 2022

*All photographs by my grandfather, Benjamin Gomes Casseres, except those of my parents, with their cameras, on top of the Christoffelberg, the highest hill on the island, and of their editing machine – that are by unknown photographers.

photo by my grandfather Benjamin Gomes Casseres - from the nineteen forties